TEXTS BY

Eugenio Alberti Schatz e Denis Curti

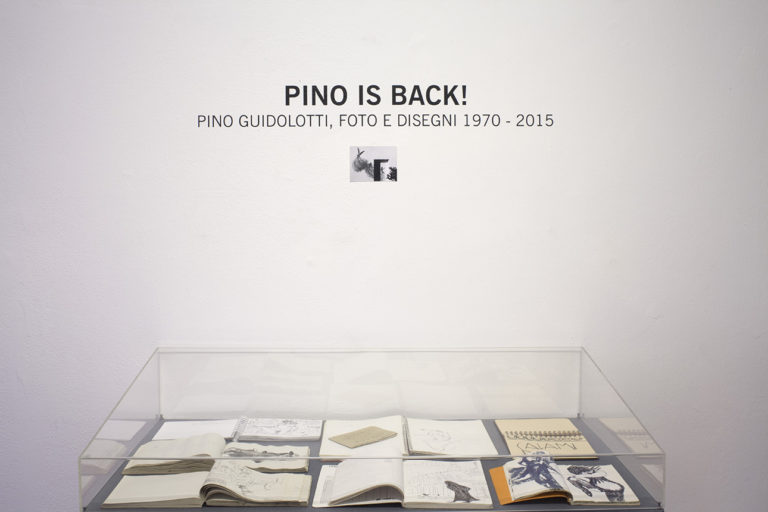

Pino Guidolotti, a versatile and unconventional artist who has captured an entire generation through his eyes of a protagonist, is back with recent and previously unexhibited work.

Leading fashion photographer in the 80s and 90s, Guidolotti has portrayed celebrities, artists, directors, architects, designers and actors; he ha salso masterfully conveyed iconic places, architecture and great sculpture from Palladian Villas to the work of Bernini.

La vera audacia consiste nell’essere interamente se stessi.

Man Ray

Uno sguardo affilato, inquieto, perennemente insoddisfatto, che scava, raschia e indaga come un bracco italiano alla ricerca di un tartufo bianco. Pino Guidolotti si muove in quella sottile striscia di terra fra arte e fotografia che oggi può sembrare main stream ma che negli anni ’80 certamente non lo era. Si avverte un certo piglio di leggerezza, uno sganciamento dall’ossessione tecnica, il non sentirsi obbligati a “portare a casa” la bella foto e il coraggio di togliersi il corsetto dei generi (per dirla tutta, se ne infischia dei generi). Lo spirito guascone lo si coglie nelle opere, nella vita, anche nella conversazione, quando sembra soppesare più le parole da non dire che quelle da dire.

Guidolotti insegue il senso delle immagini che crea come se cavalcasse nella prateria: i suoi motori primi sembrano essere la curiosità, la gioia della scoperta, la rimozione delle gabbie mentali e un oscuro senso del bello. Per non parlare della libertà con cui sceglie temi e soggetti.

Questo spiega l’assoluta imprevedibilità delle sue campagne: due nuotatori ripresi dall’alto come se il fotografo planasse quasi per caso sopra di loro, in mongolfiera e lentamente; una celebre attrice di teatro ritratta come in una vetrina di Amsterdam; una coppia di attore e scrittrice con le dita dei piedi in primo piano; una sessione in un parco acquatico sulla Costa Azzurra sugli schiavi del leisure, che forse anticipa il gusto metafisico-sociale di Adrian Paci o al contrario si riconnette a Savinio e Sironi; la modella malinconica che scivola come un cigno sui marmi del palazzo… Le architetture, tante architetture palladiane. Le sculture, tante sculture appassionate del Bernini, che del marmo fa marzapane. E i volti, tanti, tantissimi volti, una quadreria di volti, ciascuno ripreso con un quid che ci ricorda l’intuizione di Sciascia sul potere della fotografia di cogliere l’entelechia, cioè la tensione dell’individuo a realizzare se stesso secondo leggi proprie.

Guidolotti ha fatto studi artistici, poi è sceso nell’arena della fotografia, dove comunque molto ha fatto sull’arte e dintorni, non ultima la sua amicizia con Gombrich, e quando ha riposto l’obiettivo, l’arte è venuta a riprenderselo per la collottola, come un elastico. E così si è rimesso a disegnare, a fare sculture con i materiali petrosi e arrugginiti del Salento, a copiare dal vivo fotogrammi di film… No way, dopo una vita il suo occhio è ancora affamato di bellezza. Non si è dimenticato la sezione aurea e non ha smesso di mettersi umilmente al servizio di un’idea dell’armonia che ci deve pur essere da qualche parte, vicino o lontano. E che gli umani, per loro stessa natura, non possono fare a meno di sognare. Questa è la lezione superbamente semplice di un maestro. Welcome back, Pino!

“True audacity lies in being entirely oneself.”

— Man Ray

A sharp, restless gaze—forever unsatisfied—that digs, scrapes, and investigates like a trained Italian hound in search of a white truffle. Pino Guidolotti navigates that fine strip of land between art and photography—a space that might seem mainstream today but was anything but in the 1980s. There’s a certain lightness to his approach, a detachment from technical obsession, a refusal to feel bound to delivering the “perfect shot,” and above all, the courage to break free from genre constraints (truth be told, he couldn’t care less about genres).

His irreverent spirit is present in his work, in his life, even in conversation—where he seems to weigh more carefully the words he won’t say than those he does.

Guidolotti chases the meaning of images like a rider galloping across open plains. His driving forces seem to be curiosity, the joy of discovery, a rejection of mental cages, and a mysterious sense of beauty—not to mention the utter freedom with which he chooses themes and subjects.

This explains the delightful unpredictability of his photographic campaigns: two swimmers captured from above, as though the photographer were drifting over them in a balloon; a celebrated stage actress posed like a figure in an Amsterdam window; a couple—an actor and a writer—framed with their toes in the foreground; a photo session at a water park on the Côte d’Azur portraying the slaves of leisure, perhaps anticipating Adrian Paci’s metaphysical-social sensibility—or perhaps linking back to Savinio and Sironi; a melancholic model gliding like a swan across marble floors…

Architecture—so much Palladian architecture. Sculpture—so much impassioned sculpture, especially Bernini’s, where marble becomes marzipan. And faces—countless faces—a whole gallery of portraits, each one captured with a quid that recalls Leonardo Sciascia’s intuition: photography’s unique ability to grasp an individual’s entelechy, the inner drive toward self-realization.

Guidolotti studied art before stepping into the arena of photography, where he often circled back to art itself—his friendship with Gombrich being a notable example. And when he finally put the lens away, art came back for him, grabbing him by the collar like a rubber band snapping back. He returned to drawing, sculpting with rusted and stony materials from the Salento, sketching film stills from life… After all these years, his eye remains hungry for beauty. He hasn’t forgotten the golden ratio, and he continues—humbly—to serve an ideal of harmony that surely exists somewhere, near or far. An ideal that humans, by their very nature, cannot help but dream of.

This is the wonderfully simple lesson of a master.

Welcome back, Pino.

Forse un giorno la fotografia, se glielo consentiremo, ci mostrerà quel che la pittura ci ha già mostrato, il nostro autentico ritratto, e donerà allo spirito della rivolta, esistente in ciascun essere realmente vivo e sensibile, la sua voce plastica duratura.

Man Ray

In anni abbastanza recenti sei stato spesso in India. Che cosa ha rappresentato per te?

L’India mi ha fatto conoscere le puzze. Ci sono stato per otto anni di fila, dai venti ai trenta giorni ogni volta. Ho anche letto dei manuali di simbologia indiana, ma non mi è rimasto molto, si vede che non mi sono impegnato abbastanza. E in fondo, la parte esoterica non mi interessava molto. Mi interessava fotografare. Il progetto è nato da John Eskenazi, uno dei più importanti dealer di arte orientale di Londra. L’ho conosciuto in occasione di un ritratto a lui e suo padre, antiquario di via Montenapoleone, commissionatomi da Vogue. Con lui si parlava a lungo di quale doveva essere il punto di vista e di come superare i problemi, per esempio come evitare le interferenze dell’arredo urbano o quali tempi per la luce impostare, visto che noi si andava nel mese del cielo di plastica, quando la luce è monotona, senza mai una nuvola e ricorda un sacchetto bianco della coop. L’India è viaggi, fatica, spostamenti, non c’è sempre c’è il Taj Mahal ad aspettarti. Certo, nulla rispetto alla fatica che avevano fatto gli antichi a realizzare certe meraviglie. Alcune volte capita che arrivi a un sito, un tempio, una caverna, e ti domandi come diavolo avessero fatto a partorire queste meraviglie armati di un semplice martellino.

Che emozioni ti suscita la scultura indiana, a te che hai mirabilmente ritratto le statue del Bernini?

La scultura indiana è deformata. Bernini mantiene le proporzioni umane, rispetta la matematica, imprime sempre la stessa forma, la stessa sintassi. In India invece abbiamo le danzatrici a forma di svastica, sempre in movimento, i Ganesh obesi con la proboscide, e gli Shiva bellissimi, eleganti, immobili, che ti guardano dall’alto con un leggero sorrisetto. Sembrano dei radiatori. Credo ci sia un nesso fra i due mondi, si tratta solo di scoprirlo. Stiamo parlando di manufatti dell’uomo.

Spostiamo un po’ indietro la lancetta del tempo. Che rapporti hai avuto con la moda? Ti piaceva fare servizi di moda?

Era un lavoro come un altro. Alla fine degli anni ’80 ho lavorato con una certa continuità per i giornali. Dovevo fare un servizio ogni settimana. In particolare, con Vittorio Corona, direttore di King e Moda, si era stabilita una bella intesa. Mi lasciavano completamente libero, ero apprezzato proprio per il fatto di essere estraneo al sistema della moda. Non avevo realizzato nemmeno un catalogo per uno stilista! Io ero interessato alla questione scenografica, alla messinscena teatrale se vuoi. Insomma, ero un privilegiato.

Uno dei filoni forti del tuo lavoro è il ritratto di persone che sono implicate con architettura, arte, letteratura, teatro… Perché ti ha appassionato tanto il ritratto?

Il ritratto è prima di tutto un incontro. Ci si stringe la mano, ci si siede, si beve qualcosa, si inizia a parlare… Molto spesso il ritratto è anche un’autopsia visiva del loro ambiente, delle case in cui vivono o dello studio in cui lavorano. Per fare uno scatto, capitava di stare con loro una giornata intera… Poi c’è sempre qualcuno che ti spinge in una direzione, le cose non succedono a caso. Renato Olivieri, scrittore lui stesso e papà del commissario Ambrosio, impersonato al cinema da Ugo Tognazzi, dirigeva l’inserto Millelibri, dell’editoriale Giorgio Mondadori. Fu lui a incoraggiarmi, voleva che fotografassi gli scrittori a casa loro. Così feci Sciascia a Racalmuto, Eco a Milano… Sciascia fu molto gentile e paziente con me, seppi solo dopo che era già molto malato. Poi ci fu il capitolo dei designer: Ettore Sottsass, Aldo Cibic… E poi gli artisti. Mi ricordo che andavo in via Paolo Sarpi alla sera per incontrare Mario Merz, sempre incazzato nero con l’umanità. I personaggi della scena culturale sono egocentrici, e si prestano volentieri solo se sanno che vanno a finire su un giornale. Altrimenti è difficile.

Perché a un certo punto hai mollato il colpo e sei andato via da Milano?

Milano non mi dava più niente come lavoro. Guardavo il ponte di via Farini e l’edificio basso delle ferrovie lì accanto, e mi sentivo alla periferia di Bratislava. Per tirarmi su, andavo al Cimitero monumentale a passeggiare fra le tombe, ci sono un sacco di donne nude, sai, anche se di marmo…

E così hai riparato in Salento, a Minervino. Visto da qui, difficile non pensare a un autoesilio, a una sorta di Aventino. Come te la sei cavata nella tua vita post-milanese?

C’è voluto un po’ di tempo per acclimatarmi, per un po’ di tempo non ho scattato fotografie. Poi, a poco a poco ho cominciato a guardarmi attorno e ho ripreso in mano la macchina. I vecchi fotografi fotografano gli alberi. Dopo gli alberi c’è stato Giuseppe, giardiniere, un vero personaggio, un po’ anarchico, forte lettore, ai tempi insegnante di educazione fisica. Non ha un carattere facile, mi ricorda mio padre, che sopportava all’infinito ma era sempre molto arrabbiato ed era costretto a fare ciò che non gli piaceva (mio padre era maggiordomo). Penso che Giuseppe sia un mio alter ego. L’altra eccezione è per un cacciatore che andava in bicicletta, mi è piaciuto come si è comportato e mi è venuta voglia di ritrarlo. Gli ho chiesto di puntare il fucile contro il cielo. In entrambi i casi, mi ha dato soddisfazione. Al sud hanno ancora una concezione solenne dell’immagine, si mettono in posa con fare importante, come i selvaggi o come noi nell’800. Non hanno paura della fissità della posa. E infatti acquisiscono una bellissima postura.

Difficile credere che tu sia stato fermo a lungo…

Infatti, ho cauterizzato il distacco dalla fotografia con il ritorno al disegno. Io sono nato disegnando, non è stato difficile. È come quando ciò che pensavi perso nel fondo del mare ritorna a galla una volta tolti i pesi che lo tenevano giù. È una cosa naturale, un affioramento. D’altronde, non ho mai dimenticato il rettangolo aureo di quando studiavo scenografia: lo schermo fotografico è la stessa cosa. Anche solo per guardare una foto ti devi mettere alla distanza giusta. È un boccascena. Come in teatro, dove il punto di vista ottimale è posto a una volta e mezzo la diagonale. Ah dimenticavo, c’è stata un terza eccezione: la foto del bagnetto alla mia nipotina, Nina, quando aveva poco più di un anno. Sembra un battesimo. Questa è l’ultima foto che ricordo.

La mostra ad Assab One non ti fa venire voglia di tornare alla fotografia?

Sì, mi piacerebbe rimettermi dietro l’obiettivo. E voglio comprarmi una macchina fotografica analogica. Ma certamente il mio approccio è cambiato. Oggi le cose mi trovano, mi vengono addosso, non sono io che devo andare a cercarle. Giuseppe è qui ed è il mio specchio, io mi rivedo in lui. Gli odori mi trovano, mi raccontano. Ho letto tre libri di matematica, io che non capisco nulla di numeri. La serie di Fibonacci mi affascina molto e ho scoperto che gli alberi ne sono influenzati in qualche modo. E gli scacchi, quel gioco per cui non ho mai avuto tempo… Non si può mica morire senza sapere come si gioca.

A proposito di influenze, chi sono stati i fotografi che sentivi vicino?

Romeo Martinez è stato per me un padre putativo. Era un catalizzatore formidabile a livello internazionale. Abbiamo passato molto tempo insieme, grazie a lui ho conosciuto i grandi fotografi del mondo. Poi direi Paolo Monti, un bocconiano doc molto acculturato che aveva una marcia in più, pur essendo nato come amatore. Willie Ronis era molto intelligente. Enzo Sellerio mi piaceva, era bello, alto.

E le tue ascendenze culturali, i maestri a cui hai guardato?

Mi ha sempre interessato la fotografia surrealista. Senz’altro Man Ray. E poi Alvarez Bravo, ero molto attirato da lui.

Perché ti sei avvicinato alla fotografia?

Credo che la fotografia, come per altri come me che venivano dalla provincia, fosse un modo per uscire, per scappare. Uno dei miei primi reportage fu a Marsiglia, non avevo soldi, dormii in stazione, mangiai pane e patate, e andai sul molo a vedere le navi. Un modo eloquente per dire che volevo fuggire dal mio ambiente provinciale, non ti pare?

Grazie alla macchina fotografica, ti sei fatto degli amici importanti. Come Ernst Gombrich.

È una storia molto bella, quella della nostra amicizia, che si è protratta per decenni. Lui e la moglie Ilse si sono affezionati a me, forse perché come loro ero un migrante. Io mi bevevo le sue parole, ascoltarlo è stato un privilegio grande. Diceva che lui scriveva i libri pensando a un solo lettore, Panofsky. Nel 2002 al Warburg Institute è stata organizzata una commemorazione e in quell’occasione sono stati esposti i miei ritratti dal 1977 al 1996. Sull’invito hanno usato la foto in cui lui è su una scaletta da biblioteca e tiene aperto un grande in folio. L’immagine perfetta che definisce l’uomo di cultura mentre cerca di elevarsi e di elevare.

Che cosa pensi della grande diffusione che oggi ha l’immagine fotografica?

La gente sa guardare meglio di una volta, sa leggere le immagini, ha più strumenti di volta, senza dubbio. D’altronde è più facile guardare che leggere. Però non sarei così sereno. Sono belle e orribili tutte queste immagini, miliardi di scatti fatti con il telefonino. Pensa solo alle immagini che ci manda l’Isis, sono immagini porno. Ti fa vedere le cose che non puoi vedere o non vuoi v edere.

Ma nell’essenza, che cos’è una fotografia?

È una copia della vita. Se impari a copiare bene, forse col tempo diventi anche un creativo. E poi è un luogo di solitudine e di silenzio. A differenze del cinema, dove stai sempre in mezzo agli altri, come in gita scolastica, e devi gridare, dare ordini, fare sfuriate, metterti d’accordo. La fotografia è un messaggio da decifrare, sopra ci sono segnate alcune cose. Il quadro è un oggetto vivo, sente le variazione della luce. La fotografia è un cadavere, un oggetto bello e puro.

Hai mai fotografato un morto?

Mio padre. È una foto che mi piace. Il soggetto non si muoveva, non è stato difficile. È sepolto a Montefiascone, e lì abbiamo celebrato il funerale. Su questo ti voglio raccontare una storia, che sarebbe molto piaciuta a Danilo Kish. Devi sapere che sempre io ho una cotta per Curzio Malaparte, c’è stato un periodo in cui non si poteva dire perché era bollato come fascista. Leggendo la sua biografia, ho scoperto che il furgone dell’ospedale portava la sua bara da Roma a Prato fece una sosta a Montefiascone, dove gli autisti si fermarono a mangiare. Vedo nitidamente gli autisti che si abboffano, mentre fuori c’è Malaparte morto dentro il furgone.

I tuoi rapporti coi giovani?

Io sono sempre inattuale. Loro sono i miei lettori ideali.

Prima mi hai detto che sei nato disegnando. Che cosa intendevi esattamente? E come sei passato alla fotografia?

Disegnavo sui tavoli di marmo, a casa di mia nonna. Copiavo i fumetti. I velieri, soprattutto i velieri mi piacevano un mondo. Allora a Verona i due unici negozi di fotografia avevano vetrine opulente piene di macchine rigorosamente tedesche, come le Leica o le Rolleiflex. Poi, per i poveri, c’era una macchina autarchica orribile, la Bencini. Inutile dirti che la mia prima macchina fu una Bencini. Solo a Bologna, durante l’Accademia, ebbi finalmente una Nikon F.

Che ricordi hai del tuo periodo di studi all’Accademia di Bologna?

Eravamo in pieno ’68, c’erano assemblee dalla mattina alla sera. Io arrivavo da Verona e mi infilavo nei cinema per vedere i matinée. Per darti un’idea del clima che si respirava, all’esame di scenografia ho portato un testo di Marivaux tutto segnato con le mie note. Mi hanno chiesto di fare una sintesi, e io mi sono rifiutato, dicendo che il mio lavoro era la produzione di quell’oggetto. Ho lasciato perdere il diploma. Poi però il professore mi fece lavorare come assistente al Teatro Comunale di Bologna.

Ti ricordi la tua prima mostra di fotografia?

La mia famiglia paterna è del viterbese, per la precisione di Capodimonte, che si affaccia sul lago di Bolsena. Mio zio era il capo dei pescatori. A Capodimonte c’era un piccolo macello dove si uccidevano vacche e maiali. Il sangue e la morte non mi hanno mai impressionato più di tanto. Ho usato il bianco e nero. Le foto le ho esposte all’Accademia di Bologna, dove studiavo.

Ci sono dei posti dove vorresti andare?

Il Nord. Sogno di andare a Nord. Il Nord della Scozia, per esempio.

Sei in cerca di rarefazione. Allora non è vero che mordi?

Alla fine dei conti, sono una persona gentile.

“Perhaps one day photography, if we allow it, will show us what painting has already revealed: our true portrait. And it will give lasting form to the spirit of rebellion that exists in every truly alive and sensitive being.”

— Man Ray

In recent years, you’ve travelled often to India. What did it mean for you?

India introduced me to smells. I visited for eight years in a row, staying twenty to thirty days each time. I read Indian symbology manuals, but little of it stuck—I suppose I didn’t try hard enough. To be honest, the esoteric side never interested me much. I was there to photograph.

The project was conceived with John Eskenazi, one of London’s foremost dealers in Oriental art. I met him when Vogue commissioned a portrait of him and his father, an antique dealer in Milan. We spent a lot of time discussing the point of view—how to avoid interference from urban furniture, what kind of light to work with, especially since we were shooting during what I call the ‘plastic sky’ season, where the light is flat, cloudless, like a Coop supermarket bag.

India means travel, fatigue, endless movement—not every day ends at the Taj Mahal. Still, nothing compared to the ancient effort it took to create such wonders. Sometimes you arrive at a site, a temple or a cave, and you can’t help but wonder how on earth they managed to carve all that armed with just a chisel.

What emotions does Indian sculpture stir in you—as someone who has so masterfully photographed Bernini’s statues?

Indian sculpture is deformed. Bernini always maintains human proportions, respects mathematics, follows a consistent form and syntax. In India, on the other hand, we have swastika-shaped dancers in perpetual motion, obese Ganesh figures with trunks, and elegant, still Shivas who gaze down with a faint smile. They look like radiators.

I believe there is a link between these two worlds—we just need to uncover it. After all, these are all human artifacts.

Let’s move back in time. What was your relationship with fashion? Did you enjoy shooting fashion stories?

It was a job like any other. In the late ’80s, I worked regularly for magazines. I had to shoot a story every week. I had a great working relationship with Vittorio Corona, editor of King and Moda. They gave me total freedom—precisely because I was an outsider to the fashion world. I hadn’t even shot a single lookbook for a designer! What interested me was the scenographic side of things, the theatrical mise-en-scène, if you will. In short, I was privileged.

One of the strongest threads in your work is the portrait—of people linked to architecture, art, literature, theatre… Why this fascination?

Portraiture begins with an encounter. You shake hands, you sit down, you have a drink, you start talking… Often, the portrait becomes a visual autopsy of someone’s environment—their home, their studio. Sometimes I would spend the entire day with a person just to get one shot.

And then there’s always someone who nudges you in a certain direction. Things don’t happen by chance. Renato Olivieri—writer and creator of Inspector Ambrosio, played in film by Ugo Tognazzi—was editor of Millelibri, a supplement of the Giorgio Mondadori publishing house. He encouraged me to photograph writers at home. That’s how I ended up shooting Sciascia in Racalmuto, Eco in Milan… Sciascia was very kind and patient with me. Only later did I find out he was already very ill.

Then came the designers—Ettore Sottsass, Aldo Cibic… and later, the artists. I remember going to via Paolo Sarpi in the evenings to meet Mario Merz, who was always furious with humanity. Cultural figures are egocentric, and they’ll only agree to be photographed if they know the image will end up in a magazine. Otherwise, it’s hard.

At a certain point, you left Milan. Why?

Milan no longer gave me anything. I’d look at the bridge on via Farini and the low railway building beside it and feel like I was in the suburbs of Bratislava. To lift my spirits, I’d stroll through the Monumental Cemetery—so many nude women there, even if they’re made of marble…

And so you retreated to Minervino, in Salento. It’s hard not to see it as a kind of self-imposed exile, a personal Aventine Hill. How did you adjust to post-Milan life?

It took some time to settle in. For a while, I stopped taking pictures. Then, gradually, I started looking around again and picked up the camera. Old photographers photograph trees. After the trees, there was Giuseppe—the gardener. A real character, a bit of an anarchist, a voracious reader, once a PE teacher. Not easy to get along with. He reminds me of my father—infinitely patient, yet always angry and trapped in a life he didn’t choose (my father was a butler). I think Giuseppe is my alter ego.

The other exception was a hunter who rode a bicycle. I liked how he carried himself, and I felt the urge to photograph him. I asked him to aim his rifle toward the sky. Both gave me great satisfaction. In the South, people still have a solemn view of the image. They pose with dignity—like savages or like us in the 19th century. They’re not afraid of stillness. In fact, they adopt a beautiful posture.

Hard to believe you stayed still for long…

Indeed, I cauterized the separation from photography by returning to drawing. I was born drawing, so it wasn’t difficult. It’s like when something you thought lost at the bottom of the sea resurfaces once you remove the weights. It’s a natural resurfacing.

After all, I never forgot the golden rectangle from my scenography studies. The photographic frame is the same. Even to look at a photo, you need the right distance—it’s a proscenium. Like in theatre, where the optimal viewpoint is one and a half times the diagonal.

Oh—and there was a third exception: the photo of my niece Nina’s bath, when she was just over a year old. It looks like a baptism. That’s the last photo I remember.

Has this exhibition at Assab One made you want to return to photography?

Yes, I’d like to get back behind the lens. And I want to buy an analog camera. But my approach has definitely changed. These days, things find me—they come toward me. I don’t go looking for them anymore.

Giuseppe is here, and he’s my mirror—I see myself in him. Smells find me, they tell me stories. I’ve read three books on mathematics, even though I don’t understand numbers. The Fibonacci sequence fascinates me, and I’ve discovered that trees, in some way, follow it. And chess—that game I never had time for… You can’t die without knowing how to play.

Speaking of influences—what photographers have felt close to you?

Romeo Martinez was like a godfather to me. He was an incredible catalyst at the international level. We spent a lot of time together, and thanks to him I met some of the greatest photographers in the world.

Then there was Paolo Monti, a true Bocconi man—highly cultured, and with something extra, even though he started out as an amateur. Willie Ronis was very intelligent. I liked Enzo Sellerio—he was tall, handsome…

And your broader cultural lineage? The masters you looked up to?

I’ve always been drawn to surrealist photography. Certainly Man Ray. And also Manuel Álvarez Bravo—he fascinated me deeply.

Why did you first turn to photography?

For me, and others like me who grew up in the provinces, photography was a way out—a means of escape. One of my first photo essays was in Marseille. I had no money, slept in the train station, ate bread and potatoes, and wandered the docks watching ships. It was a way of saying—without saying—that I wanted out of my provincial world. Don’t you think?

Thanks to your camera, you’ve made some important friends. Like Ernst Gombrich.

Yes, it’s a beautiful story—our friendship lasted for decades. He and his wife Ilse became very fond of me, maybe because I, like them, was a migrant. I drank in every word he said. Listening to him was a rare privilege.

He used to say he wrote his books with a single reader in mind: Panofsky. In 2002, the Warburg Institute held a commemorative event, and my portraits from 1977 to 1996 were exhibited. They used a photo of him for the invitation: Gombrich standing on a library ladder, holding open a large folio. The perfect image of a man of culture—trying to elevate himself and others.

What do you think about the overwhelming circulation of images today?

People are better at looking now—they have more visual literacy, more tools. No doubt about it.

And looking is easier than reading. But I wouldn’t be too optimistic. All these images—they’re beautiful and horrific at once. Billions of photos taken with phones. Just think of the images sent out by ISIS. They’re pornographic in a way. They show you what you shouldn’t—or don’t want to—see.

At its core, what is a photograph?

It’s a copy of life. If you learn to copy well, maybe you’ll become a creator over time. But it’s also a place of solitude and silence.

Unlike cinema, where you’re always surrounded by people—it’s like a school trip: shouting, arguing, giving orders, negotiating. Photography is a message that needs to be deciphered; some things are marked on it.

A painting is a living object—it senses changes in light. Photography is a corpse—a beautiful, pure object.

Have you ever photographed someone who had passed away?

My father. It’s a photo I like. The subject wasn’t moving—so it wasn’t hard.

He’s buried in Montefiascone, where the funeral was held. Let me tell you a story about that—it’s something Danilo Kiš would have appreciated.

You know I’ve always had a soft spot for Curzio Malaparte. There was a time when you couldn’t say that out loud—he was labeled a fascist. While reading his biography, I discovered that when the hospital van carried his coffin from Rome to Prato, the drivers stopped in Montefiascone for a meal.

I can see it clearly: the drivers stuffing themselves while Malaparte lies dead in the van outside.

And your relationship with young people?

I’m always out of sync. But they’re my ideal readers.

Earlier, you said you were born drawing. What exactly did you mean? And how did you move into photography?

I used to draw on marble tables, at my grandmother’s house. I copied comics. Sailboats—I adored drawing sailboats.

Back then, in Verona, the only two photo shops had lavish window displays filled with German cameras—Leicas, Rolleiflexes.

And for the poor, there was the horrible autarkic Bencini camera. Needless to say, my first camera was a Bencini.

Only in Bologna, while at the Academy, did I finally get my hands on a Nikon F.

What do you remember about your studies at the Bologna Academy?

It was 1968. There were assemblies all day long. I had come from Verona and spent my mornings in cinemas watching matinees.

To give you an idea of the atmosphere: at my scenography exam, I brought in a text by Marivaux, filled with my notes. When they asked me to summarize it, I refused. I said that the marked-up script was my work. I didn’t get my diploma.

But the professor later hired me as an assistant at the Teatro Comunale in Bologna.

Do you remember your first photo exhibition?

My father’s family is from the Viterbo area—specifically Capodimonte, on Lake Bolsena. My uncle was the head of the fishermen there. Capodimonte had a small slaughterhouse where cows and pigs were killed.

Blood and death never bothered me. I shot in black and white. I exhibited the photos at the Bologna Academy, where I was studying.

Are there any places you still dream of visiting?

The North. I dream of going North. Northern Scotland, for example.

So you’re searching for rarefaction. Then it’s not true that you’re fierce?

At the end of the day, I’m a gentle person.

Martinez is, in my humble opinion, the father confessor of many photographers

who came to him begging for absolution. His greatest sin is never having asked

them for any offerings for his worship of photography. He knows each of us better

than we know ourselves.”

Henri Cartier-Bresson.

Difficile collocare Pino Guidolotti all’interno dei ristretti generi della fotografia: paesaggio, ritratto, reportage, street photography, moda, still life… anche perché il nostro li frequenta tutti e come un decatleta ottiene ottimi risultati nei diversi ambiti. Calciatore mancato, anche se di grande talento, è stato uno dei protagonisti della fotografia milanese degli anni ottanta, per poi sparire dalla scena trasferendosi al sole della Puglia. Disegnatore, fotografo e affabulatore Guidolotti è oggi il maestro assoluto della sottrazione. Non solo perché si è sottratto dalla fotografia, ma perché credo davvero che sia un vero poeta della sintesi. I tratti (disegni) e le sue immagini (in bianco e nero) sono un raro e nobile esempio di un lavoro a togliere che mira all’essenza totale.

Resta, comunque, quell’inflessione veneta che lo rende meno credibile e dopo poco che lo conosci, capisci che vorrebbe essere sempre da un’altra parte. Irrequieto, solitario, curioso. Ma se lo interroghi a fondo e con pazienza, alla fine, scopri che non è proprio così. Lui sta fermo sul bordo di un’ipotetica fotografia e ti guarda, ti annusa, ti misura e se decide che ci sei (davvero) allora anche lui rimbalza come una pallina da flipper e comincia a raccontare.

La prima cosa che mi dice riguarda Romeo Martinez (da qui la citazione iniziale). Erano amici, così come è stato (lo è ancora?) amico dei grandi della fotografia, dell’arte, della letteratura, del cinema e del teatro. Con Martinez, grande direttore della rivista Camera tra gli anni cinquanta e sessanta, Guidolotti condivide una complicità progettuale che, di rimando, lo riporta al rigore e all’austerità di Paolo Monti. Il percorso è tortuoso e me ne rendo conto. Ma è proprio dalla ruvidità delle cose, dall’attrito tra i pensieri che posso nascere certe immagini. Quella di Guidolotti è una fotografia totale. Le sue fotografie, mi pare, nascono da un’urgenza interiore. Guidolotti si esprime secondo criteri estetici precisi per creare relazioni, interazioni e restituire l’idea di un sentimento trasversale capace di sviluppare armonia, equilibrio e forse precarietà. Forse è per questo che se ne è andato, forse è per questo che è ritornato.

Denis Curti – marzo 2015

It’s hard to place Pino Guidolotti within the strict categories of photography—landscape, portrait, reportage, street photography, fashion, still life…

He moves fluidly between them all, like a decathlete achieving excellence in each discipline. Once a promising footballer—though ultimately a missed vocation—he became a central figure of the Milanese photography scene in the 1980s, only to withdraw from it entirely, retreating to the sun-drenched lands of Puglia.

A draughtsman, photographer, and storyteller, Guidolotti is today the undisputed master of subtraction. Not only because he stepped away from photography, but because his entire practice—whether in drawing or in black-and-white images—is rooted in poetic reduction. His work embodies a rare and noble exercise in removing the superfluous, relentlessly pursuing essence.

And yet, that lingering Venetian inflection still gives him away, makes him seem less plausible. Spend a little time with him, and you realise he’s always yearning to be somewhere else. Restless, solitary, curious. But if you probe a bit deeper—with patience—you discover that’s not quite true. He remains poised, on the edge of an imaginary photograph, watching, sniffing the air, sizing you up. And if he decides you’re really there, he springs into motion like a pinball and begins to tell his stories.

The first thing he mentions is Romeo Martinez (hence the opening quote). They were friends, just as he has been (perhaps still is?) close to some of the greats in photography, art, literature, cinema, and theatre. With Martinez—the brilliant editor of Camera magazine in the ’50s and ’60s—Guidolotti shared a spirit of creative complicity that also echoes the rigour and austerity of Paolo Monti.

Yes, the path is winding. I’m aware of it. But it is from the roughness of things, from the friction of thoughts, that certain images are born. Guidolotti’s is a total photography—images that, I believe, stem from an inner urgency. He expresses himself through precise aesthetic criteria, forging connections and relationships that give shape to a transversal sentiment—one capable of conveying harmony, balance, and perhaps even a sense of fragility.

Maybe that’s why he left. Maybe that’s why he came back.

Denis Curti – March 2015

Pino Guidolotti is one of the most famous Italian photographers. During his career he has worked with major Italian newspapers and publishing houses ranging from fashion, portrait, architecture. Moreover, he has devoted his attention above all to art and reproduction of the artistic heritage, also influenced by the his long friendship with Ernst H. Gombrich.

MONOGRAPHS

A.Rosenauer, Donatello. Opera omnia, Milan 1993.

R.Wittkower, Bernini. The sculptor of the Roman Baroque, Milan 1990, London 1997.

Beltramini. Andrea Palladio: Atlas of Architecture, Venice 2000.

G.Beltramini e H.Burns. The Venetian Villas, Venice 2005.

M.A. Avagnina. The Teatro Olimpico in Vicenza, Venice 2005.

Progetto Viven, 200 Venetian Villas

Davide Gasparotto, The horses by Francesco Mochi.

John Eskenazi, The Classical India sculpture.

SOLO EXHIBITIONS (selection)

2014. Inaugurazione di me stesso, Cinema del Reale, Specchia (LE)

2006. Volti di Architetti, Yellow Fish Gallery, Montreal.

2006. Volti di Architetti, Centro Palladio, Vicenza.

2005. Le Ville Venete, Centro Palladio, Vicenza.

2003. Carlo Scarpa. L’opera, Centro Palladio, Vicenza.

2001. Le ville del Palladio, Centro Palladio, Vicenza.

2001. Memorial E. H. Gombrich, Warburg Institute, London, U.K.

2001. Pino Guidolotti, Galleria Il Diaframma, Milan.

2001. Pino Guidolotti, Casa del Mantegna, Mantova.

2001. Pino Guidolotti, Photographer Gallery, London, U.K.

2001. Pino Guidolotti, Musèe Reattu, Arles, France.

2001. Photographie Italienne, Chalon sur Saone, France.

2001. Pino Guidolotti, Galleria Il Diaframma, Milan.

1974. Pino Guidolotti, Krakow, Poland.